Introduction¶

Most programmers are familiar with code written as functions that take arguments that subsequently call more functions that take more arguments. In order to call a function you need to know what arguments to provide, and in addition that function needs to know what arguments to provide to functions it calls and possibly add them to its own argument list to be passed in.

MDF turns this around and provides a way of expressing code as a directed acylical graph, or DAG for short. Each node in the graph depends on other nodes, which ultimately may depend on a set of terminal nodes that represent the input values to the graph or sub-graph.

This is best explained via a brief example. Consider this set of simple Python functions:

def A(x, y, z):

return B(x, y) + C(y, z)

def B(x, y):

return x + y

def C(y, z):

return y * z

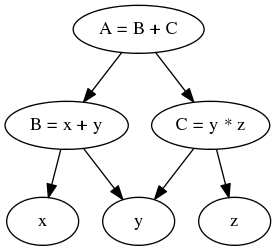

This can be expressed as the following graph:

In the first case evaluating A(1, 2, 3) is simply a case of calling the

function. In the second case, we evaluate the node A under the condition

x=1, y=2 and z=3.

Consider that now the definiation of C is not quite right, it’s decided it

should actually be:

def C(x, y, z):

return x * y * z

Because of this change to C, now A has to changed. If it has required

another argument then A would also have to have its arguments changed and

and functions calling A would have to be updated:

def A(x, y, z):

return B(x, y) + C(x, y, z)

def B(x, y):

return x + y

def C(x, y, z):

return x * y * z

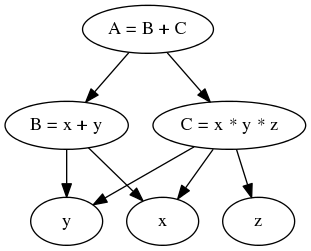

In the graph based approach node C can be changed without impact on A,

and provided all dependents of C exist in the graph there is no change

required to the calling code.

Now consider that you want to evaluate A for a set of z. Using the

traditional approach you could call A(x, y, z) for each z in the

required set. Now assume that you also want to collect the values of C for

that set of z as well as A. At this point you have a few choices. You

might call A and C for each z, you might refactor A to take

C as an argument so you only have to compute C once for each z, or

you might refactor A to take a list as an argument and accumulate the

results of C in that.

Let’s assume you end up with something like this:

def A(x, y, c):

return B(x, y) + c

def B(x, y):

return x + y

def C(x, y, z):

return x * y * z

x = 1

y = 2

for z in range(100):

c = C(x, y, z)

a = A(a, y, c)

print a, c

Now you notice that computing B every time is expensive and unnecessary. You

refactor out B to improve performance:

def A(b, c):

return b + c

def B(x, y):

return x + y

def C(x, y, z):

return x * y * z

# set the static variables x and y

x = 1

y = 2

# pre-compute b as it doesn't vary with z

b = B(x, y)

# compute A and C for each z

for z in range(100):

c = C(x, y, z)

a = A(b, c)

print a, c

This is a contrived example, but even so it’s starting to feel untidy and every

other reference of A and B needs to be refactored.

In contrast doing the same evaluation using mdf is quite straightforward. Below is some example code using mdf that does the same as the code above. Don’t worry that some terms referenced in this code have not been mentioned yet, this is just to give an idea of how this code can be written:

from mdf import MDFContext, varnode, evalnode,

# varnode creates nodes that have values in a context

x = varnode()

y = varnode()

z = varnode()

# @evalnode declares that these functions are nodes in our DAG

@evalnode

def A():

return B() + C()

@evalnode

def B():

return x() + y()

@evalnode

def C():

return x() + y() + z()

# contexts are covered later in these docs, but essentially it's where the

# values for the nodes are kept

ctx = MDFContext()

# set the values for x and y in the context

ctx[x] = 1

ctx[y] = 2

# compute A and C for each z_i

for z_i in range(100):

ctx[z] = z_i

# getting the values from the context evaluates them and returns the results

print ctx[A], ctx[C]

Nodes are evaluated lazily and only re-computed when their dependecies have been

updated. This means that in the example above B is only calculated once as

x and y aren’t changed.

If B was modified so it was dependent on z, or any other changes for

that matter, the code above wouldn’t have to be changed outside of the

definition of the actual node being changed. In the more traditional version

changes in a function may require corresponding changes to the calling code

which is not always immediately obvious.